by Ray Linville

It’s scuppernong time. The historic grape is ripe and ready across the state in grocery stores, at roadside stands, and from u-pick-it vineyards—along with other varieties of the muscadine.

Autumn means it’s time to appreciate and enjoy these indigenous grapes. They sustained Native Americans, European explorers and colonists, enslaved and indentured workers, and many recent ancestors who were much more dependent on the land for food than a quick trip to the grocery store.

Lately I noticed “grapes for sale” signs popping up along the road literally as soon as Labor Day arrived. These signs typically refer to the scuppernong or another muscadine variety. Stopping for grapes usually results in more than buying the grapes themselves. With a little luck, you can learn a story or two about the families that grow them.

Meet George Whellis, 74, who lives within the city limits of Wilmington where he has grown several varieties of scuppernong and muscadine grapes for decades. He strategically places signs on a busy street like real estate agents do. However, he wants to entice passersby to stop and pick from the rows of grapes behind his house.

When I followed the signs to his home, I didn’t have time to pick, so he kindly gave me about two pounds of grapes – free — that he had just picked. (Talk about being lucky!) I spent the time that I didn’t have to pick by talking to him about his fondness of the native grapes and his goals of eventually conducting wine-making classes in his home.

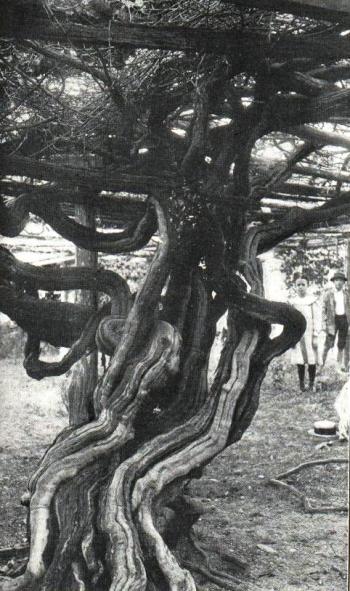

When Whellis moved to Wilmington, he brought several grape cuttings with him. He had lived in Pamlico County, not too far from the 400-year-old scuppernong “mother vine” on Roanoke Island that is regarded as the oldest cultivated grapevine in the world. His vines have thrived ever since and produce a bountiful harvest every fall.

Whellis is also quick to distinguish muscadines – “they’re black,” he says – from its scuppernong variety that is bronze or golden. In addition to the scuppernong, Whellis grows several other muscadine varieties — the Noble, Nesbitt and Supreme.

His family has enjoyed muscadine varieties for generations. Although Whellis grew up in Wilson, early ancestors settled in the Yadkin Valley region near Lowgap. His family members are like many native Tar Heels who are taught at a young age how to eat the scuppernong and muscadine, both notorious for crunchy seeds and thick skins. The secret: Hold a grape with the stem scar up. Next bite or squeeze the grape into your mouth. As the pulp and juice burst through the skin into your mouth, savor the fruity flavor — but be careful to avoid chewing the bitter skin. (Spit out the skin and seeds if you wish — or simply swallow them as some people do.)

Although Whellis enjoys eating the grapes themselves, he has developed a fine reputation as a winemaking hobbyist. His homemade wine typically is given away to friends and family, but it has been enjoyed as far away as the West Coast by Chinese businessmen visiting the CEO of a tech company (who had been given a bottle by Whellis’ son). “The Chinese [businessmen] really enjoyed the muscadine flavor,” Whellis says.

North Carolina celebrates its muscadine and scuppernong heritage each September in Kenansville. In 2015, more than 25 vineyards, cellars and wineries that sell muscadine and scuppernong wines, jams and other products participated – attesting to the growing popularity of these grapes. When I visited the festival recently, I gained a greater appreciation of how many people in our state are enjoying them.

Some u-pick-its, such as Bruton Vineyard in Eagle Springs, open as early as late August. Most have scuppernongs available for picking until mid-October. Take time to pick your own. But if you can’t, at least enjoy the scuppernong and other muscadine varieties while they are fresh.

Resources

Popular Muscadine Cultivars in North Carolina

What are the months to pick scuppernongs?