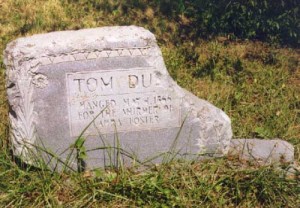

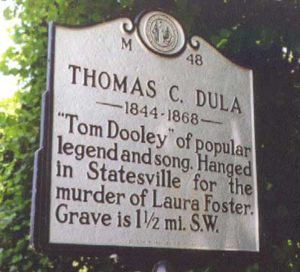

On this day in history – May 1, 1868 – Thomas C. Dula was hanged in Statesville, NC for the murder of Laura Foster. Dula (pronounced “Dooley”), the bloody murder, and subsequent trial became the infamous subjects of the “Ballad of Tom Dooley.”

On this day in history – May 1, 1868 – Thomas C. Dula was hanged in Statesville, NC for the murder of Laura Foster. Dula (pronounced “Dooley”), the bloody murder, and subsequent trial became the infamous subjects of the “Ballad of Tom Dooley.” ![]()

![]() Much has been written over the years about the actual murder, the ballad, and American murder ballads in general.

Much has been written over the years about the actual murder, the ballad, and American murder ballads in general.

(And if you meander through the links in this post, you will see a young Michael Landon as Tom Dooley, learn about the role of syphilis in the murder, and all kinds of other historical goodies.) Today we’re also interested in how the folk performer – collector – researcher – mainstream media relationship connects to a controversy this week over at the New York Times Magazine.

Who owned Tom Dooley?

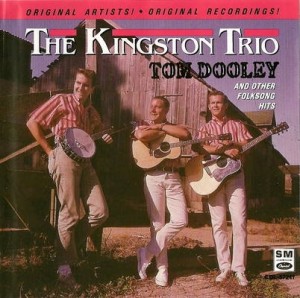

According to Chuck Shuford, The Kingston Trio’s version of the song “Tom Dooley” in 1958 had “an almost unprecedented impact on American musical tastes” that created “fundamental change in popular music and culture.” The ballad wended its way toward international renown the way many elements of folk culture do — courtesy first of a collector who records a traditional artist singing or playing a song, then through a researcher who makes the find public. In this case Frank Proffitt, a farmer and dulcimer maker in Watauga County, was recorded singing Tom Dula by Frank Warner. (By the way, Warner, an avid collector of folk songs, was a student of Duke University’s Frank C. Brown, who founded the North Carolina Folklore Society.)

Now Proffitt never claimed to write the song — he learned it from his aunt, Nancy Prather, and Grayson and Whitter had even recorded a version in 1929. But it was Proffitt’s version Warner recorded, and then shared with folklorist and archivist Alan Lomax, who published it in Folk Song, USA (arrangement credited to Frank Warner).

Pete Seeger described Alan Lomax as “the man who is more responsible than any other person for the twentieth-century folk song revival,” and from here the song made its way into the repertoires of 1950’s pop groups, including The Kingston Trio. (Great in-depth overview of the song’s travels here.)

Pete Seeger described Alan Lomax as “the man who is more responsible than any other person for the twentieth-century folk song revival,” and from here the song made its way into the repertoires of 1950’s pop groups, including The Kingston Trio. (Great in-depth overview of the song’s travels here.)

Folk Music USA‘s publisher initially sued The Kingston Trio for copyright infringement. In the ensuing out-of-court settlement, Frank Warner and Frank Proffitt also received royalty agreements, one of the few times a traditional performer received monetary benefit from a pop group’s interpretation of his recording.

“Quasi-Theft” in 2014

Earlier this week, Susannah McCormick sent a furious email letter to the New York Observer in response to a New York Times’ Magazine cover article by writer John Jeremiah Sullivan.

McCormick castigates Sullivan and former research assistant Caitlin Love for stealing material from her father — music researcher Robert McCormick –about the enigmatic blues musicians Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas.

“John Jeremiah Sullivan and Caitlin Love wormed their way into the home of an elderly invalid under the guise of ‘helping him,’” Ms. McCormick said, alluding to the undergraduate research assistant who helped Mr. Sullivan acquire the documents via “quasi theft,” as Mr. Sullivan put it, “then proceeded to rifle through his files and help themselves to his research, his photographs and his personal possessions. There is no disputing these facts because Sullivan admitted as much in his own article.”

So once again we have a controversy related to rightful ownership of folk culture — does it belong to the traditional artist who performed or talked about her work, to the avid collector, or to the researcher who made the information public?

Sullivan told the Observer in a phone conversation that he believes he is legally in the clear. “You can’t own somebody else’s speech,” Mr. Sullivan explained. “It’s actually her [L.V. Thomas’s] speech in the transcripts and not his writing.”

Well, that is actually a tricky subject. The Rights of Writers site asks, “Who owns an interview?” “It is clear that most interviews are copyright-protected. . . . But who is the copyright owner of the resulting give and take of questions and answers? The interviewer who formulates the questions? … The interviewee who provides the answers?” Or maybe the interview (and subsequent transcript) forms a kind of “joint work” in which both parties share ownership.

Before Susannah McCormick’s letter (continued in this essay published Tuesday), the response to Sullivan’s article was overwhelmingly positive. The writing is great (and so nice to see long-form supported), the story and information about Geeshie and Elvie fascinating, and the online format — with audio clips embedded in the texts and interspersed multimedia — glorious.

Once the criticism came to light, people found their doubts raised. Rather than debate whether Sullivan (or Love) did anything unethical, I am more interested by how the debate has been framed — as the value of the rights of McCormick (right to do what he chooses with his stuff, right not to be taken advantage of) vs. the interests of the public. Here is a taste of the arguments on both sides, from the comments section of the Observer article:

Taking possession of something that belongs to someone else without due process of Law is morally and ethically wrong despite the most energetic rationalizations. Sometimes it’s even ethically and morally wrong when done with due process of Law.

McCormick has been known as a cultural horder (sic) for decades and there is something very wrong with taking this stuff to the grave with you.

Shame on any scholar that withholds their knowledge. It’s not theirs to keep.

Almost no one in this debate raises the rights of the original artists — of Geeshie and Elvie (or Lillie Mae Wiley and L.V. Thomas, as we learn in the article). Of the commenters, only American Studies professor Charles McGovern argues that Sullivan “let himself off the hook too easily” in large part because L.V. herself did not want her blues history known. (Sullivan points this out himself: “the truth I forget more often than any other, in thinking about this — L.V., too, wanted it hidden.”

The framing of the discussion as concerning the rights of two white men, both published authors, serves only to re-marginalize the supposed subjects of the piece and underscore the role of power and privilege. Whether you agree with the perceived wrong done to McCormick, it is certainly true that his assertion of intellectual property theft easily found public expression in the pages of the New York Observer, and with next-to-no questioning about the legitimacy of his “owning” the stories, and photographs, and other materials of vernacular artists.

It is almost certain that Frank Proffitt would not have received royalties from Tom Dooley if Alan Lomax’s publisher had not sued for copyright infringement. We folklorists, musicologists, archivists, and other culture researchers can become more focused on the value of the recordings, transcripts, and ephemera of folk artistry that we collect and preserve than the folk artists themselves and whether they are treated equitably.

White folks sometimes discover their unexamined white privilege for the first time when unexpectedly asked for i.d. or made to wait in line. The outrage over being treated unfairly provides an opportunity to notice what a common experience it is for others. The McCormick family’s outrage reminds me of this response — doesn’t the gathering of material from others with the assumption that he knows best what they are worth and what they are good for basically describe McCormick’s collecting career?

***

Additional reading:

Ballad of Tom Dooley, by Sharyn McCrumb

Historical account of the case by Harry McKown, UNC Libraries

Saga of a Folksong Hunter, by Alan Lomax

The Collector and Still Has the Blues – two earlier articles about Robert McCormick

John Jeremiah Sullivan’s response to controvery (published just a few hours ago)

This is thought-provoking, but a bit wrong-headed. The article by Mr. Sullivan — which, as you note, was an excellent piece of writing and a wonderful use of web publishing — most assuredly took nothing whatsoever from Elvie and Geeshie, as they were credited on their records. Both are deceased. It is not clear to me that living people have a right to control their history, but it is very clear that dead people have no such right.

Mr. Sullivan in no way misused the artwork produced by these women, who had already sold the rights to that art to a record company. Though one might certainly question whether the recording business in those days was fair to artists, that is not a problem that one can lay at the feet of Mr. Sullivan. He simply brought the artistry of these women to a brand new audience. I had never heard of them before reading his article, as I am sure is the case for most who read it. And he gave their art even more power, by allowing us to understand, more than anyone has ever understood, who they were.

As for the charges of “theft” from Mr. McCormick, most of the material gathered by Mr. Sullivan and his assistant was wholly original research in public records. McCormick’s material merely provided leads, not answers. McCormick himself shared some of the material with Mr. Sullivan and, later, with his then assistant. Unless McCormick had Ms. Love sign a non-disclosure agreement before taking her on as an assistant, he has no legitimate complaint. Had Mr. McCormick published the contents of his trove of research, he would own a copyright to it. As it is, the best one can hope is that Mr. Sullivans’ article has helped Mr. McCormick’s family realize the value of his collection, and that they will donate it, at the appropriate tim, to an institution of higher learning, rather than hauling it to the landfill.

There are a lot of misplaced concerns in this article.

“So once again we have a controversy related to rightful ownership of folk culture…”

Actually, it appears the controversy is whether Sullivan and Love copied a manuscript that didn’t belong to them, without permission, and then published an article partially based on this “quasi-theft” (as the author himself refers to it). The question is about the rights of an author to control his or her manuscripts, not who owns “folk culture.”

“Almost no one in this debate raises the rights of the original artists — of Geeshie and Elvie (or Lillie Mae Wiley and L.V. Thomas, as we learn in the article).”

Because they are dead. The controversy is about an alleged theft from one living person by another living person.

“The framing of the discussion as concerning the rights of two white men, both published authors, serves only to re-marginalize the supposed subjects of the piece and underscore the role of power and privilege.”

Would it be better if white men just not write about black artists at all? The only reason anyone knows anything about these artists is: McCormick did the research. Sullivan’s article (based on that research) actually takes the women out of the margins of nothingness and gives them a skeletal biography. By excoriating Mccormick as a privileged white man, you are implicitly approving of the women remaining anonymous names on an old label and nothing more. McCormick was the *only* person in the USA who actually made an effort to prevent that from happening.

“White folks sometimes discover their unexamined white privilege for the first time when unexpectedly asked for i.d. or made to wait in line. The outrage over being treated unfairly provides an opportunity to notice what a common experience it is for others. The McCormick family’s outrage reminds me of this response — doesn’t the gathering of material from others with the assumption that he knows best what they are worth and what they are good for basically describe McCormick’s collecting career?”

You’re obviously unfamiliar with McCormick’s history, or you wouldn’t have written this. This is not the first time he’s had his research appropriated without consent. As for the question, see above. If McCormick hadn’t gathered the material, probably no one would have. You apparently would have preferred that.