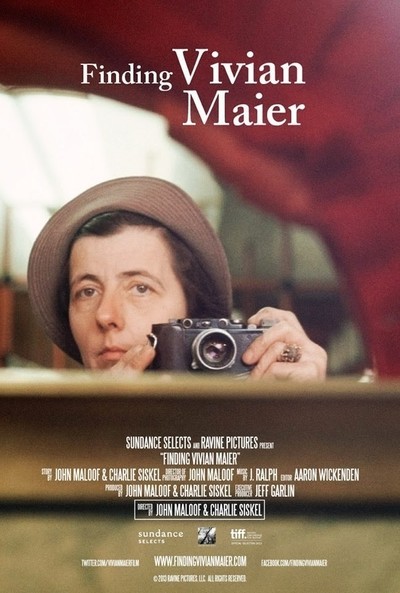

T he newly released documentary Finding Vivian Maier tells the story of John Maloof’s

he newly released documentary Finding Vivian Maier tells the story of John Maloof’s

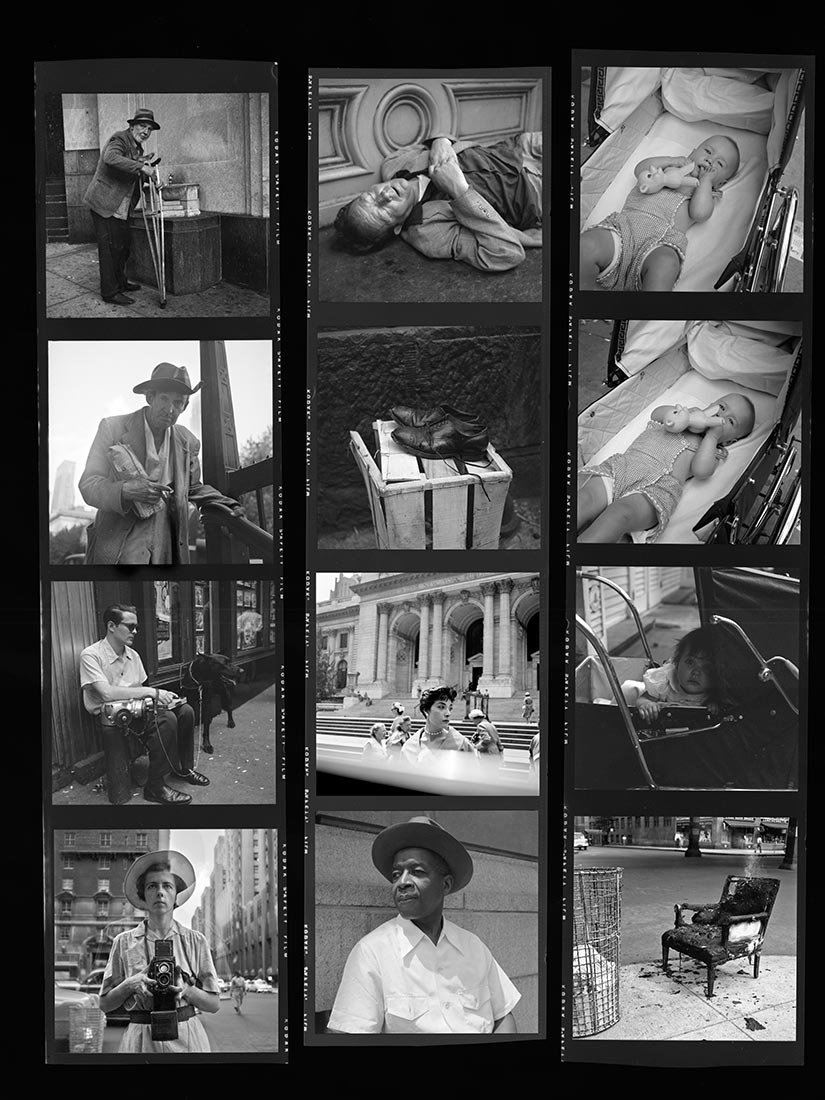

purchase of a box full of old negatives at auction, hoping they would relate to the book he was writing about his Chicago neighborhood. Instead, they led him to the discovery of street photographer Vivian Maier. As Maloof learns more about her work (which is stunning), he tries to uncover more about the woman as well. The film paints a portrait of an eccentric recluse, a hoarder, a woman who not only did not share her photos with others but may have been openly opposed to them being seen.

Jillian Steinhauer at Hyperallergic stated in April, “it’s to Maloof’s credit that he unearths all of this, and much more. His obsessiveness is a perfect complement to Maier’s: what she collected and shrouded in mystery, he has discovered and determined to bring to light.”

However, last week Steinhauer posted an update at Hyperallergic called “The Vivian Maier ‘Discovery’ Is More Complicated Than We Thought.” Though much of the post concerns the extent to which Maloof is or isn’t cutting out or working with the other two men who had also acquired significant collections of Meier’s work, it also ponders who should have the right to share documentary materials and who should have the power to curate them. One collector says, “We are in an age where the curators want to be stars, and often become via storytelling, but the bottom line is, it’s the artist who is the shining light. Vivian Maier is that light.” But by all indications, Maier wanted neither to illumine nor be illuminated.

Brian Tallerico centers his review of the documentary around this conflict, saying, “And so I’m incredibly torn about “Finding Vivian Maier” overall. Should Maloof and [Charlie] Siskel have opened a door that a dead woman so clearly wanted locked?” Tallerico finds that the “film raises the question of privacy regularly with people who knew Maier commenting on how much she would have loathed this investigation into her life and Maloof wondering aloud if he’s gone too far” and concludes that curiosity is not sufficient cause for invasion of privacy.

This reminds me of my earlier post about the ethics of the documented, which asked whether folk culture belongs “to the traditional artist who performed or talked about her work, to the avid collector, or to the researcher who made the information public?”

In that post, I was referring to an article in New York Times Magazine in which it is John Jeremiah Sullivan who discovers an intriguing mystery in a little-known artist and pursues her back-story, despite knowing that the subject of his quest “wanted it hidden.”

As in Steinhauer’s description of the “complications” of Vivian Maier’s discovery, the controversy surrounding Sullivan’s piece about early blues women Geeshie and Elvie centers around the arguments of white male collectors, scholars, or researchers as to which of them have the right to share and interpret materials of those who have gone on. There is less questioning of the most appropriate or ethical role of the discoverer or curator in general.

Who has the right to “make meaning” of others’ lives and stories is an ongoing question for all folklorists. The issue of control underlies this question — control of the narrative as well as of the materials themselves. Steinhauer points out, “Maier is no longer alive (nor does she have any descendants), which means the printing and presentation of her work and story are controlled almost entirely by the private collectors who own her effects — none of whom she knew, let alone chose to represent her.” Indeed, Maloof’s website is subtitled “The Official Website of Vivian Maier.”

When dealing with effects of people who have died, it is easy to get look for answers only in legalities of copyright and ownership. But similar questions play out all the time in art, folklore, anthropology, and related fields. Who has the right to say what the story “means?” Who has the right to choose to publish or publicize? What is more important, the monetary value of art, the quality of artistry itself, or what it can tell us about the culture it either comes from or documents (such as Maier’s street photography)? Once you end up with materials, do you have a responsibility to consider what their creator would want done with them or are they yours? What is the difference between acceptably benefiting from your efforts as a culture worker and unfairly profiting from those with less access to markets and power than you have?

How do you answer those questions for yourself, and how do you want people who work with your community to answer them?

You should also see the Vivian Maier film that the BBC made last year. Really wonderful and more about her and her work. http://www.vivianmaiermysterymovie.com