by Sarah Bryan

Verlie Helsabeck Freeman was a vivid woman. She had a cat named Mr. Cat, a set of dentures that she took out of her mouth and clacked at frightened great-grandchildren, and—as she warned overly curious visitors who might snoop around the house—a booger in her basement. (To readers who aren’t from North Carolina, let me hasten to explain that a booger is like a goblin, a small, scary creature unacquainted with the interior of one’s nose.) Verlie spent every year of her nearly century-long life in North Carolina—born in a cabin in the shadow of Pilot Mountain near Rural Hall, raised at the foot of the Uwharries in the Montgomery County crossroads of Ether, a young married woman at a lumber camp somewhere in the Piedmont, and, in later years, a resident of Ellerbe, Creedmoor, and Durham. She could easily have been mistaken for a South Carolinian, though, for better or for worse, given the adamance of her opinions. Among her convictions was a rule about how coffee should taste: “Black as hetcher, and strong as agafortis.”

By the time I would have been old enough to get to know her, Verlie, my great-grandmother, was far off into dementia, so most of my impressions of her are second-hand. I’d like to have asked her about hetcher and agafortis. It’s easy enough to interpret: clearly hetcher, whatever it is, is very black—I used to assume it was like “heck,” a euphemism for hell—and you can see the palisades of the fort in agafortis, so that must be something very strong. But the exact etymology of the phrase was mysterious. When I took my first folklore class as a freshman at George Washington University, right away I asked the professor—John Michael Vlach, the mentor whom I have to thank for my becoming a folklorist—if he’d ever encountered the phrase “black as hetcher and strong as agafortis.” He hadn’t, but the next week, after class, he pulled me aside and said, “Okay, I’ve got it.”

John explained that it referred to elements of the etching process. “Hetcher” referred to an etcher—the metal plate that is etched upon and which, when painted over with a solution of asphaltum, is as black as the darkest coffee you could drink without croaking. Since Verlie was from the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, it makes sense that she’d pronounce “etcher” with an aspirate, like the mountain “hit” for “it.” “Agafortis” was a corruption of “aqua fortis,” or nitric acid, a corrosive used to etch into the plate. (It was also used in alchemy, being strong enough to dissolve most any metal other than gold; for that you would need aqua regia.) Where Verlie would have encountered these terms originally, I don’t know. Most of her forebears were Moravians in and near Salem, North Carolina, a community known for artisanship in many fields, so it’s not impossible that there may have been a (h)etcher in the family somewhere along the line.

Verlie’s oldest son was my grandfather Belmont, born when she was 15 years old. Belmont attended the University of North Carolina, where he did his graduate work in philology, specializing in Old French. As a graduate student he taught a French class, and one of his students was his future wife, my grandmother. Her maiden name is María Magdalena Susana Kjellesvig Waering y González, but she’s always been known in the family as Malala, or Lala. (I think this dates to when she was learning to speak, and had trouble saying “Magdalena.”)

Malala and Belmont could hardly have had more different backgrounds if they were John Rolfe and Pocahontas. Belmont grew up in rural and small-town Piedmont North Carolina, his father being a storekeeper (not a very successful one, because, it’s remembered of him, he couldn’t stand to take his customers’ money away from them when they bought things from him). His native section of Montgomery County was a place where the old ways of healing by herbs and incantation long took precedence over the doctoring of medical professionals, where your neighbors seemed exotic if they went to a different church, where most evenings you’d have peas and cornbread for supper but might kill a chicken if the preacher were coming to visit.

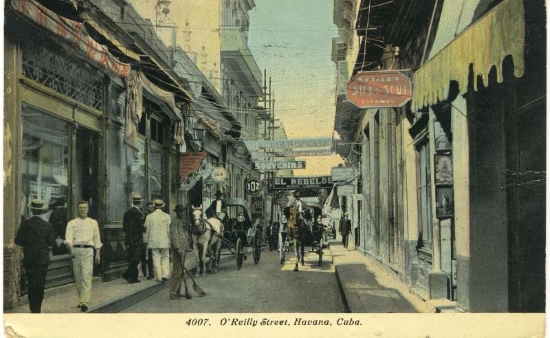

Malala, on the other hand, spent most of her growing-up years in Havana, Cuba. Her mother came from an old Havana family who owned cigar factories, exported leather, and ran certain municipal operations, and had the means to send their children overseas for necessities like education and avoiding tropical epidemics. Her father was Norwegian, an engineer who despised cold weather and, as soon as he finished his degree at the University of Trondheim (only about 200 miles south of the Arctic Circle), booked it to Latin America. Needless to say, my grandmother’s upbringing was cosmopolitan, multilingual, and very multi-cultural, a far cry from life in the beautiful but tiny and remote crossroads of Ether, North Carolina. There was at least one way, though, that Malala’s and Belmont’s families were alike: both liked their coffee black as hetcher and strong as agafortis.

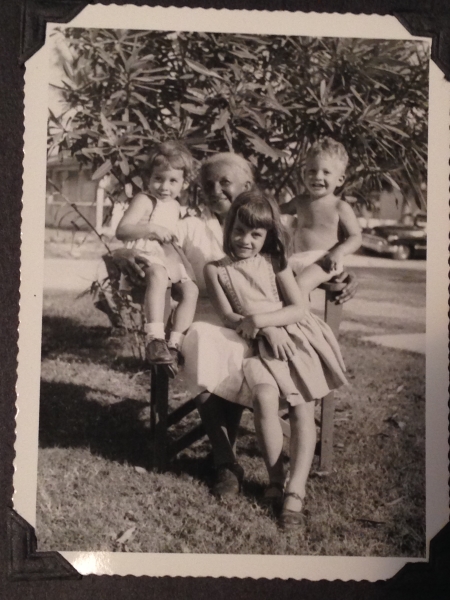

In Cuba the family lived in Vedado, an early twentieth-century neighborhood near the old center of Havana. Making the household’s morning coffee was the job of the cook, Juaquina González. (She shared the family’s last name because during slavery, which didn’t end in Cuba until 1886, her mother Sofía had belonged to my grandmother’s grandmother.) Juaquina went daily to the corner bodega to buy the coffee, and had the beans ground in small quantities so it was certain to be fresh. The tradition was that the first cup of coffee every morning went to Pancho el Flaco (Skinny Pancho), my grandmother’s aunt’s chauffer. He had a special cup that stayed in the kitchen and that only he was allowed to use. Then the parlor maid Clementina (she and Pancho were both white, while Juaquina, though considered black, clearly had Spanish blood too) would serve coffee to all the family, adults and children alike. She knew the amount of milk (lots) that each person took, and so the morning coffee was actually café con leche. Malala’s Norwegian father had a special fondness for Cuban coffee, and he would have a second course of coffee in the afternoon.

I know everyone thinks that his or her grandmother is the greatest cook ever; but mine, Malala, actually may be. She didn’t begin to learn until she and my grandfather became engaged and, in preparation for life as an American homemaker, asked her mother for help. Her mother was hardly an expert—she’d grown up in a household where Sofía, Juaquina’s mother, was the cook—but she knew enough to get Malala started. First lesson: boiling an egg. “Pon un caldo a hervir,” said her mother, “Set a pot to boil.” That was her introduction to the mysteries of the kitchen. By the time my grandparents got married in 1943, The World’s Modern Cookbook and Kitchen Guide for the Busy Woman was in its third printing, and that was a big help. Cuban cookbooks at the time had instructions like, “Combine ingredients, cook until done,” so it was probably a little while before Malala was ready to tackle Cuban recipes, but when she did, she found what would become one of her areas of specialty. She makes truly wonderful moros y cristianos (“Moors and Christians,” black beans and rice), ropa vieja (“old clothes,” tomatoey shredded beef), and flan (the Latin equivalent of crème caramel), among other culinary cubanidades.

What did Malala and Verlie, her mother-in-law, think of each other’s cooking? Neither one quite got where the other was coming from, so to speak. Malala remembers the first meal that she ate at her in-laws’ home: “Mixed greens—collards and this, that, and the other—with pork in it. I ate it just to be polite. The only ‘green’ I’d ever heard of was spinach. Now I know that I would like it. Sweet potatoes. Pork of some kind. Biscuits, of course, and I loved them.” (The pork and biscuits would have been familiar—pork is a basic seasoning and main dish in Cuban food as well, and though biscuits as such don’t appear on Cuban tables, the cuisine is renowned for the delicious and deceptively simple crusty white bread served with meals.) Verlie, for her part, “wouldn’t touch my cooking because it had onions and garlic and tomatoes in it.”

All four of Malala’s and Belmont’s children—my mother Cristina, aunts Cissy and Luisa, and uncle Monty—are exceptional cooks too. My mother, a Virginian, learned to cook in her dad’s native North Carolina, and married a Lowcountry South Carolinian, so her cooking draws heavily from Southern cuisine, but with a strong Cuban influence. For all of us—all of Malala’s cooking children and grandchildren—most any savory dish begins with a sofrito, a mixture of garlic, onion, and green pepper sautéed in olive oil. Anything with a sofrito base can and does go on rice, a staple of both the Lowcountry and Latin America, so we all buy basmati in bulk. The Cuban-Carolinian table has obvious roots in Africa: rice, sweet potatoes or yams (or the closely related Cuban boniato), peanuts (maní in Cuba), okra (quimbombó), set-aside pot licker, fritters of all sorts.

I myself am much too limited and picky in my eating ever to be a chef of my mom’s and grandmother’s caliber—a strict vegetarian, near-vegan, I won’t go near most vegetables either—but the elements of my cooking that do work tend to be in that same realm, where the Cuban and Carolinian intersect. Here’s one of my favorites. It’s great for wintertime, full of Vitamins D and C, which help you fend off colds and seasonal depression, and remind you of hot weather.

…………………………………………………………………………………………

Carolinian-Cuban Collard Greens

Wash and de-stem two or three large bunches of collard greens, and cook them in salted boiling water. How long you’ll cook them probably depends on your family background: if you’re from the South, don’t hesitate to cook them for hours on end, until they fall apart like wet Kleenex. (That’s how I like them.) If you’re from somewhere else, and/or want the finished product to be visually appealing, you might want to boil them for half an hour or so, or just until tender.

Drain collards, and set aside the pot licker (the water, now a grayish-green color, that the greens were boiled in). It’s full of vitamins that have boiled out of the collards, and you can freeze it and use it as a delicious, dark-tasting base for vegetable soup. Just make sure the collards are well-drained. (Once they’re cool you can even wring them out like a washcloth—whatever it takes to get most of the moisture out).

In a large skillet, make a sofrito: heat a couple of tablespoons of olive oil, and add finely chopped garlic and onions. (For this recipe, I omit the green pepper usually in a sofrito.) When the garlic and onions are soft and fragrant, add a cup or more of chopped fresh tomatoes, with their liquid (important!), and cook on medium heat for a couple of minutes.

Add the collard greens to the pan, sautéing on medium heat until the tomato’s liquid has thoroughly soaked and suffused the greens. You may also want to add a good tablespoon of tomato paste, to amplify the tomato flavor. A dash of lemon juice is also good. Season to taste with adobo, an herb-blended salt that you can find in the Latin section of the “international foods” aisle of any grocery store. I like a whole lot of adobo, but it’s very salty, so add it a little at a time, testing the flavor as you go.

If you’re not a vegan, pour in a handful of crumbled feta cheese. When the cheese has melted into the greens, remove from heat.

Serve over—or better yet, mixed into—white rice.

…………………………………………………………………………………………

Sarah Bryan is a folklorist and lives in Durham, North Carolina. sarah-bryan.com

Photo by Peter Honig: Sarah Bryan and Miss Landers Honig at the Davie Poplar, on the campus of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Leave a Reply