Text and photos by Ray Linville

Whiteville, the largest city in Columbus County and the county seat, has been a hub of activity in eastern North Carolina since the county was formed in 1808. When vehicle traffic came onto the scene, major highways U.S.74, 76, and 701 intersected in the downtown section and brought tourists, courthouse business, and retail customers, all hungry at lunch for a quick, satisfying bite.

This setting proved to be beneficial for Kermit Ward who began operating a grill on South Madison Street in the 1950s. About a mile away from the now 100-year-old county courthouse and around the corner from the railroad station (now renovated as a special-event venue), Ward’s Grill then would have attracted a lot of visitors as well as locals. It was also a good place for a teenager such as Junior McKeel to work, and McKeel has continued to work there for 50 years.

“I was 16 years old when I started working here,” McKeel says about Ward’s Grill, which he didn’t rename when he bought it in 1972. Today when customers enter and approach the counter, they see a father-daughter team busy at work. McKeel keeps the grill going while his daughter Kandle Rogers takes orders, bags the food, and manages the cash register. The narrow space barely gives them enough room to maneuver behind the counter. Perhaps as wide as 10 feet, it almost seems as if you can touch both side walls if you tried.

Ward’s is distinctive because it has no room for customers to sit down. All orders are bagged to go. However, the lack of space doesn’t discourage a dedicated following of customers such as Charlie Duncan, 64, a native of Whiteville, who has eaten at Ward’s Grill “all his life.” He says that he eats there “five days a week—always a cheese dog and a cheeseburger.”

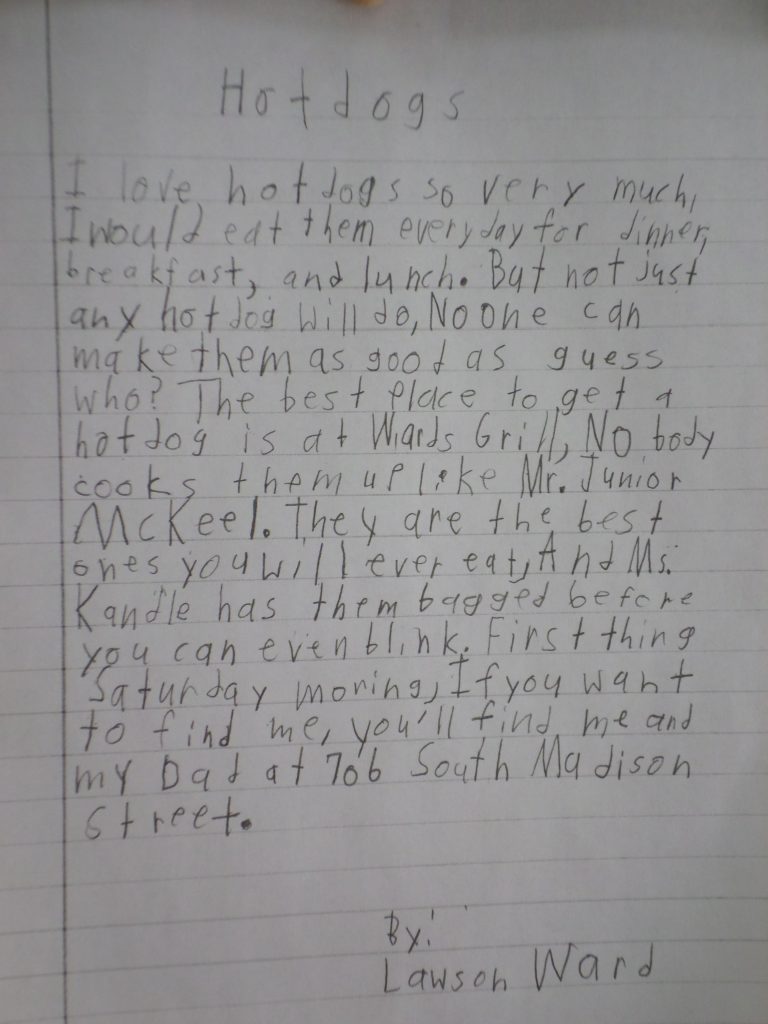

The typical customer stays only a matter of minutes—just the time to place an order, pay for it, and leave. Duncan is the exception; he eats at the edge of the counter (leaving room for the next customer to order) and watches the constant motion of the father-daughter team. Hot dogs and hamburgers are the fare at lunch (breakfast sandwiches are sold early in the morning when the grill opens) and are served as speedily as customers enter and leave. Rogers can bag hot dogs “before you can even blink,” according to Lawson Ward, a third grader, whose letter of praise is posted prominently on one of the grill’s walls.

In 1972 when McKeel bought Ward’s, 400 to 500 hot dogs were sold each day plus the hamburgers. He estimates that about 300 hot dogs now are sold a day. The decline occurred as manufacturing plants closed in the area. “We lost all the factories,” he says.

In the 1970s, a hot dog cost 25 cents and a hamburger, 35. How many of one were sold then in proportion to the other depended on the day of the month. “On the first day, we sold more hamburgers. All the local workers had just been paid. As the month went on, we sold more hot dogs—they’re cheaper,” he said.

Now the prices are much higher, but still considered a good value by dedicated customers. A hot dog costs $2.10 (add 50 cents for cheese, the way that Duncan likes it), and a hamburger, $2.85 (45 cents more for a cheeseburger). Although Duncan extols the virtues of each, I had to try the famous hot dog and ordered one “all the way,” which means chili, onions, and mustard—all wrapped in a soft, steamed bun that was so good that I want to visit again (but perhaps not as frequently as Duncan).

“Not just any hot dog will do. No one can make them as good as guess who? Nobody cooks them up as good as Mr. Junior McKeel,” according to the young student, who likely will continue to be a regular customer of Ward’s Grill for a long time. Even though fast roads such as U.S. 74 and 76 now bypass the downtown area, the loyal local customer base should keep Ward’s thriving.

Leave a Reply