(Post title comes from Seeger’s song, “To My Old Brown Earth”)

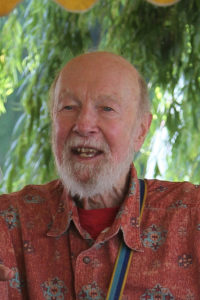

Last Monday morning sometime after six, I heard the radio talking about Pete Seeger’s career and said aloud, “Oh, no.” Throughout the day and week I read many tributes and memorials in the news and on websites, which followed similar themes. First we highlighted the personal connections (here in North Carolina, the Folklife Institute was not the only organization to point out that he first got turned on to folk music at Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville in 1935). Then we recounted what made him so important.

I have loved many of these remembrances and tributes, but they’ve also got me thinking. While we talk most about his music — as a bridge between traditional and pop cultures, as a tool for activism — I have found myself reflecting on Seeger’s legacy a little differently this week. I would argue his most important insights related to other qualities of traditional culture, which he effectively used in his activism.

Is it the music?

Last week’s tributes by and large describe Seeger first and foremost as a folk singer — Bruce Springsteen famously described him as “the father of folk music.” This tends to make us folklorists roll our eyes at what to us is an oxymoron, because folk music, like all forms of folklore, is shared with those before and after us, not drawn from whole cloth by any one person, no matter how talented.

What Springsteen really means is that Seeger may have done more than any other single individual to fuel the Folk Revival movement, so called because it was inspired by a generation of young folks discovering older traditional music and propelling their version of the sound onto the pop charts. This pop culture understanding of “folk music” has led to a general belief that the term means a particular sound or style of music – usually akin to the Kingston Trio’s take on “Tom Dooley” or the bluegrass version of a mountain standard. Of course folk music literally means “the music of the folk,” and it can refer to any style of music that exists within a community culture and holds a tension between long tradition and innovation. (Even within the sixties “folk music” scene there were forms of traditional music other than white mountain stringband music popularized — think about the work of Odetta, Josh White, and Harry Belafonte for starters.)

Often a dichotomous argument develops about the Folk Revival, where people on one side accuse participants of appropriating folk culture for fame and profit and ruining (or at least diluting) the “authenticity” of the “real” folk music. Meanwhile the other side argues that it was their parents’ Kingston Trio or Pete Seeger record that made them fall in love with a sound so much that they traced it back to its roots to discover and appreciate the traditional music that underlay it. Seeger himself pointed out that he was uncomfortable with the term folk music because it implied music of the everyday folk or “peasants,” which did not apply to this son of a Harvard-trained professor and a concert violinist trained at the Paris Conservatory of Music.

Or is it something else?

What strikes me about Pete Seeger’s career is not that he was keenly attuned to the qualities of music that made it “folk” but to many other attributes and uses of traditional culture and healthy community. Here are some examples that occur to me, and places in NC I’ve seen it used

1) Traditional culture is participatory.

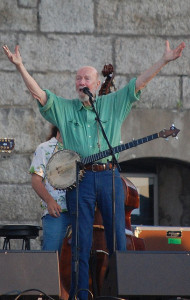

“Above all have a chorus,” songwriter Tom Paxton says he learned from Pete Seeger. You’ve got to “have something for them to sing.” Creating participatory events was Seeger’s specialty (and fits in with many musical folk traditions that emphasize inclusion, such as shape note singing, lining out hymns, and other forms of call and response).

U.S. mainstream society emphasizes consumption over interaction. Health organizations warn us that passive lives of sitting on the couch watching TV, driving, and sitting at a computer all day will lead to all sorts of problems. We know that civic engagement requires active participation, and yet we find those “third spaces” — where community exists outside home and work, where we can interact instead of just taking in — hard to come by. What people found in a concert hall with Pete was more important that a rediscovery of a particular song or a type of music; it was a rediscovery of the joy and power of lifting voices together in song. This power has never been lost, of course – and if you don’t believe it’s powerful, research the importance of song in the Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 60s. But in years since the 1960s, opportunities for this have become more and more scarce, outside perhaps church and rock concerts. Even after his voice was pretty much shot Seeger continued to hold concerts, because by that time people understood his role was not concert performer, but song leader.

How are we called to participate in our communities, and who are the leaders who can show us how?

2) Traditional culture looks back to go forward.

This concept is most succinctly summed up in the Adrinka symbol Sankofa (loosely translated “go back and fetch it”). In one image, Sankofa conveys connected clusters of meanings intrinsic to folklife and traditional culture. We cannot live in the past, but at the same time we must know our roots to move forward. If we have lost our connection to our community stories, we may need to make an effort to rediscover or reclaim them. “Whatever we have lost, forgotten, forgone or been stripped of, can be reclaimed, revived, preserved and perpetuated” (W.E.B. DuBois Learning Center).

When Pete Seeger and some friends were outraged about the polluted condition of the Hudson River in 1966, they came up with an ingenious solution.

They commissioned a sloop to travel up and down the Hudson, and from it they held concerts and environmental education events. This is another example of getting people out and participating in their communities, but the Sloop Clearwater was not only beautiful and trim, but also designed in the fashion of the historic Dutch sloops that had sailed the Hudson hundreds of years earlier.

Why? They could have gotten someone to donate a boat, or made a tongue-in-cheek (and undoubtedly cheaper) statement by converting a garbage ship. But it was important to evoke the connection of the river and of the people along it to the past. From that connection rolled many implicit messages: This has been here a long time. This matters. There are stories connected to it that you should know. You are connected to that history, that legacy, those stories. And so therefore, you are invested in making sure they continue into the future.

Whose stories and histories are told in your communities and whose have been lost or suppressed? How can retaining (or rediscovering) knowledge of the past anchor our visions for the future?

3) Traditional cultures and communities need to speak for themselves.

The reason Pete Seeger would have rather been known as a singer of folk songs than a folk singer is that he was sensitive to ethical issues of appropriation and representation. Looking over his whole career, he was always willing to speak up for himself and his personal beliefs, and he was often willing to lend his name (and banjo) to someone else’s movement and to raise his voice in someone else’s march. But he didn’t try to become a spokesperson for that community or that movement, and often objected when others cast him as such. When he championed a cause as the voice of the community, as with the Hudson River, it was a community in which he was a member. The New York Times last week called Seeger “at bottom a plain-spoken citizen of Beacon, N.Y.” As a 65-year resident of New York, Seeger picked up litter and lobbied with his town’s officials for local improvements, as well as visiting the barber shop and going to birthday parties.

Seeger saw the value in action that arises from and occurs within communities. While he certainly showed up at the big events — Occupy Wall Street, benefit concerts for everyone from Paul Robeson to migrant workers — he continually urged people to look local, whether performing in just about every school along the Hudson River or participating in Beacon’s anti-war pickets. “I don’t think that big things are as effective as people think they are,” he said. “The last time there was an anti-war demonstration in New York City, I said, ‘Why not have a hundred little ones?'” He understood that community expression isn’t just about aesthetics, but about identity. Jeff Todd Titon has a great story on his sustainable music blog about Seeger championing vernacular yard art as an art form because it “is of the people, by the people, for the people . . . . And we should celebrate it, and support it, not just by how it looks, but for what it is.”

Unlike some other celebrities, Pete Seeger never tried to “speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.” Instead, he helped to amplify their own voices by singing with them, writing them a song, or teaching them what he knew about drawing on our traditional cultures’ strengths for action.

What changes when we prioritize listening for and to traditional communities and amplifying their message, rather than prioritizing honoring them, remembering them, or helping them?

Seeing it in action in NC

Mulling all this over has brought several North Carolina groups, organizations, and movements to mind. Who would you add to this list?

The Sandhills Family Heritage Association (whose emblem, by the way, is a Sankofa Bird) — Using everything from historical maps to oral histories, Ammie Jenkins discovered that there was a different story about local land ownership than the one she had grown up hearing. A long history of African American self-sufficiency through farming and land-ownership had suffered the loss of land, often through racial intimidation. The Heritage Association documents African American history, helps communities map their cultural assets, and conducts heritage-based tours. It started a farmers’ market, an annual cultural festival, and youth programs to pass on love and stewardship of the land and its as a basis for income and self-sufficiency for rural Black communities.

The Warren County environmental movement — In the late 1970s, NC state officials selected the mostly Black community of Afton, in Warren County, for a landfill to store 60,000 tons of soil contaminated with the toxic chemical Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB). The site did not meet EPA requirements for a hazardous waste landfill. In 1982, after four years of legal action and protests failed to stop the planned dumping, hundreds of citizens and allies met the dump trucks, lying in the road to prevent delivery. Protests continued for six weeks, by which time more than 500 people had been arrested, from juveniles to senior citizens. This protest gave birth to the environmental justice movement and the term “environmental racism.”

Health initiatives by North Carolina Indian communities — Supported by the Healthy Native North Carolinians project at UNC’s American Indian Center, these varied initiatives are focused on “advancing Native health by focusing on the broader communities in which their people live, pray, study, eat, and play.” While some communities receive the message that they need to break from tradition to become healthier, NC tribes are looking to their cultural heritage, their connection to the land, and their stories to create new health programs and projects. These include community gardens growing Native plants, an annual run on tribal lands, a farmers’ and craft market, and a healthy cookbook with recipes from elders’ heritage groups.

Ocracoke Working Watermen’s Association (Ocracoke Foundation) — In 2006 the last fish house on Ocracoke Island was put up for sale, which left local watermen (and women) — those who harvest fish, clams, crabs, or oysters — with no place to unload their catch or buy bulk ice. In order to hold onto their maritime traditions and their economic livelihoods, the watermen joined together to form a non-profit and purchase the fish house. They also engage in oral history research, conduct educational programs and exhibits, and run the Ocracoke Seafood Company. The Seafood Company, which sells to several Island restaurants, allows tourists to enjoy fresh local fish, caught by hand by local watermen. Together, the waterman community has found a way to preserve Ocracoke’s maritime cultural heritage, which dates to the 1700s, while also building a community-based economic development project that benefits the whole of Ocracoke by retaining its “quaint fishing village” identity and fresh local seafood availabililty.

Pete did so many things behind the scenes. I recently learned that he was actively interested in and concerned with issues in the Middle East. He chose to donate his share of the royalties to the song “Turn, Turn, Turn,” to a group working to promote peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

When I was on the crew of the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater in about 1970 one of our fellow crew members drowned. He was a young man named Wayne, only about nineteen years old, who just went for a swim off the side of the ship and never returned. Pete showed up the next day, his face drawn, clearly heartsick over this tragic loss. He returned again with Toshi a day or two later and told us that he had set up a foundation in Wayne’s name which would provide scholarship money to young black men wanting to be doctors—as Wayne, an African American, had wanted to be. He said he had met with his parents and described them as, “wonderful young people.”

I have never again heard mention of this scholarship but I would not be surprised if it is still providing scholarships to aspiring medical students. So much of what Pete did was not known…. his public persona was just the tip of the iceberg.

Always Pete Seeger invited, cajoled, browbeat, and included the audience in singing along. When required to testify before the House (so-called) Un-american Activity Committee, Pete offered to sing for them to demonstrate what his music was all about. The Committee refused to allow that, leading TIME Magazine to comment, “thus going on record as the only people in American who did NOT want to sing along with Pete Seeger!”

Great piece Joy. Pete was the embodiment of community-based work – lifting up the community, celebrating its strengths & preserving culture & history.